As we discussed in I is for Interstellar, space colonization is a major theme of science fiction, especially space opera. Of course, things don’t always go smoothly. Space is a really, really, really big place, and sometimes, due to war or famine or simple bureaucratic mismanagement, colonies get cut off from the rest of galactic civilization. They become lost colonies.

As we discussed in I is for Interstellar, space colonization is a major theme of science fiction, especially space opera. Of course, things don’t always go smoothly. Space is a really, really, really big place, and sometimes, due to war or famine or simple bureaucratic mismanagement, colonies get cut off from the rest of galactic civilization. They become lost colonies.

Some of my favorite stories are about lost colonies: either how they became cut off, or how they reintegrate after so many thousands of years. In many of these stories, the technology of these colonies has regressed, sometimes to the point where the descendents may not even know that their ancestors came from the stars. When contact is finally made, the envoys from the galactic federation may seem like gods or wizards.

Because of this technological disconnect, stories about lost colonies often straddle the line between science fiction and fantasy. After all, Clarke’s third law states:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Of course, the line between science fiction and fantasy has always been a fuzzy one. Hundreds of attempts have been made to define it, but they all fall short. In the end, it often breaks down to certain recurring tropes, like dragons and wizards versus ray guns and rockets, but even that doesn’t always work.

For example, Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern is technically about a lost colony far into the future, but it’s got dragons and castles and other tropes that belong squarely in fantasy. Then again, the dragonriders have to fight alien worms who invade every few dozen years from a planet with a highly elliptical orbit, so there’s still a strong science fiction basis undergirding the whole thing.

And that’s just Dragonriders of Pern. What about Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Darkover series, or C.S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy? Trigun is more western than fantasy, but it’s also full of sci-fi tropes like giant sand-crawling monster ships and a weird post-apocalyptic backstory. And then there’s all the Japanese RPGs that combine magic with mechas, with Xenogears as one of the best examples. For a distinct Middle Eastern flavor, look no further than Stargate.

It’s no coincidence that all of these stories feature a lost colony of one kind or another. When the characters don’t know that they’re living in a science fictional universe, it’s very easy to throw in tropes from other genres. By no means is it required–Battlestar Galactica and Dune are evidence enough of that–but they certainly present the opportunity to do so. After all, lost colony stories basically present a hiccup in humanity’s march of progress, breaking the essential science fiction narrative for all sorts of interesting side stories and tangents.

One perennial favorite of science fiction writers is to suggest that Earth itself is a lost colony from some other galactic civilization. That forms the entire premise behind Battlestar Galactica: the original twelve colonies have been destroyed in the human-cylon wars, and the last few survivors are searching for the legendary thirteenth colony of Earth, hoping to find some sort of refuge. Apparently, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish cycle also plays with this trope, though she’s never very explicit with her world building. It can be a bit tricky to twist the lost colony trope in this manner, but if pulled off right it can really make you sit back and go “whoa.”

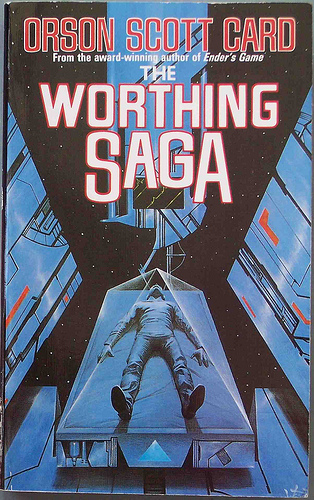

My personal favorite is probably Orson Scott Card’s The Worthing Saga, about a colony of telepaths that breaks off from a collapsing galactic empire and actually becomes more advanced than the rest of humanity. When Jason Worthing and Justice re-establish contact, the descendents of the galactics are basically pre-industrial subsistence farmers who view them as gods–which, in a certain sense, they almost are.

It’s a great story that really entranced me, not just for the science fictional elements but also for the distinct fantasy flavor. Orson Scott Card’s handling of viewpoint in that book is truly masterful, so that I felt as if I were viewing everything through the eyes of his characters. Since the farmers don’t know anything about their spacefaring ancestors, all the parts from their point of view feel like a completely different story. It was really great.

My first novel was actually a lost colony story, combined with a first contact. I trunked it a long time ago, but many of the earliest posts on this blog are all about my experience writing it. As for my other books, Desert Stars contains elements of this, though the lost colony in question is actually a nomadic desert society that lives on the capital planet of the galactic empire, just outside of the domes where all the more civilized folk live. Heart of the Nebula is basically about a society that puts itself in exile in order to escape the privations of the Hameji. And in… no, I’d better not spoil it. 😉

The lost colony isn’t one of the flashier or more prominent tropes of science fiction, but it’s definitely one of my favorites. It’s a great way to add depth and intrigue, as well as bend genres. For that reason, I think this trope does a lot to keep science fiction fresh.

I love this concept too. In fact, my own novel is based on it.

I love the mix of sci-fi and fantasy in Anne McCaffrey’s Pern stories. They were my introduction to fantasy, and I was half way into the series before I discovered they were acually sci-fi. (No internet then, so I couldn’t read ahead!) It was brilliantly done.

Rinelle Grey

Yeah, I think the Lost Colony is one of those tropes that drives the genre a lot more than we realize, just because it’s not as flashy (or perhaps because there are so many different directions you can take it). There’s also a tendency for secondary world fantasies to claim, at the end, that the whole thing is some sort of prehistoric backstory of our world, but it’s hard to pull that off without making it feel like that explanation was just tacked on.