Right after I went through my Dinosaur phase, I saw Star Wars IV: A New Hope for the first time. Instantly, all that childlike excitement and exuberance was transferred from paleontology to astronomy. We had a series of about twenty astronomy books in my elementary school’s LRC (Asimov’s astronomy series, I believe–the ones with the gray dust jackets), and in about a year I’d read them all.

Right after I went through my Dinosaur phase, I saw Star Wars IV: A New Hope for the first time. Instantly, all that childlike excitement and exuberance was transferred from paleontology to astronomy. We had a series of about twenty astronomy books in my elementary school’s LRC (Asimov’s astronomy series, I believe–the ones with the gray dust jackets), and in about a year I’d read them all.

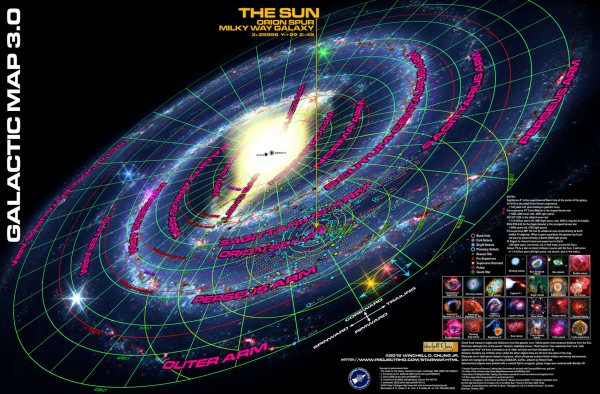

Star Wars was fun, but what was really fascinating was learning about the stars. When I started to grasp the scale of our galaxy–that if our solar system was the size of a milk carton, the Milky Way would be the size of North America–my mind was totally blown. Quasars, pulsars, black holes, white dwarfs, red giants–it was so amazing! And then, when I started thinking about all the other worlds out there, and what it would be like to visit them–that’s when I became a science fiction fan for life.

It goes without saying that you can’t have space opera without setting the story somewhere in space. But the best space opera goes much further than that–it’s about space as the final frontier, and humanity’s ultimate destiny among the stars. After all, if we as a species stay put on this pale blue dot, sooner or later we’ll kill ourselves off or suffer another mass extinction event that wipes us all out like the Dinosaurs.

For that reason, classic space opera often takes undertones of manifest destiny, except on a galactic scale. The stars are not just interesting places to visit, they’re absolutely crucial to our survival, and no matter what alien dangers await us, we will face them boldly and either conquer or be conquered.

Of course, not all space opera stories take place during the exploration and colonization phase of human interstellar expansion. Plenty of stories take place thousands of years later, once humanity has comfortably established itself among the stars. Even so, there are still more than enough wonders remaining to be explored–if not for the characters, then for the readership. The vastness of space is so great that there really is no end to it, and the possibilities are only bounded by the writer’s imagination.

One of my favorite space opera computer games is Star Control II, also know as the Ur-Quan Masters. In the game, you’re the captain of a giant starship built with alien precursor technology. The races of the Federation, including humanity, have been defeated and enslaved by an aggressive warrior race known as the Ur-Quan. You must travel from star to star, gathering resources to upgrade your starship and convincing the other alien races to join the new alliance.

By far, the best part about that game is the starmap. It’s HUGE! More worlds than anyone can possibly visit in any one playthrough, or five, or even ten. And each alien race has its own history, its own culture, its own set of goals and objectives–and oftentimes, most of these goals have very little to do with the actual conflict of the game. In fact, there are some races like the Arilou which don’t even seem to know that there’s a war going on. They’re much more interested in something frightening and mysterious from another dimension that they never quite explained, but that may involve the Orz somehow…

With each new world that you discover, you learn that the galaxy has a very, very, very long history. So long, in fact, that the human race has only really existed for a blip in time. The other races are involved in their own disputes, and many of these go back to the times when our ancestors were swinging through the trees somewhere in central Africa. But whether or not we want to be a part of it, we’re involved, simply by virtue of where our star happens to be located.

The best space opera isn’t just about our world: it’s about our place in a much wider universe. Whether it’s a serious tale about humanity’s ultimate destiny, or an action-packed intergalactic romp, there’s always that sense of something greater than us–that same sense of wonder that gripped me as a boy when I first started to learn about the stars.

Image by nyrath at Project Rho. I highly recommend checking out his excellent starmaps!

Amazing blog! So glad A to Z brought me here. Cheers! 🙂

The fact that space is so huge is amazing. I haven’t heard it quite like that, but I’ve really enjoyed doing exercises with my daughter where we take objects to represent the planets, and space them out to scale. That’s pretty amazing. There’s also a webpage somewhere where you scroll across the screen, and the planets are shown to scale. It’s easy to scroll past them by accident!

Rinelle Grey

FWIW, historians use the term ‘manifest destiny’ in ways that the tropes link only begins to convey. The term has become intertwined in many circles with imperialsim, racism, and the ugliness of westward expansion. That didn’t come across in your usage here, but I don’t know that it isn’t true of space opera and the like. What say you?

As always, I think it depends on the book. The Forever War by Joe Haldeman definitely had undertones of that, though I’m drawing a blank on other sci-fi authors who saw this sort of expansionism as a negative thing. A lot of the older writers like Heinlein actually seemed to promote it, kind of like the people who invented the term “manifest destiny” back in the 19th century.

From what I understand, the term has always been controversial, with different sides taking different positions on the issue, and while much far-future sf kind of accepts the inevitability of it, there’s a lot of different takes on it as well.

Yes to that sense of wonder!!!

Yes indeed!