Is curiosity a bad thing? Well, it depends how genre savvy you are. It seemed to work out pretty well for Alice, but not quite so well for Pandora (or the rest of the ancient Greek world, for that matter). Curious monkeys seem to come out all right, and their constantly curious counterparts also seem to do okay in the end, but anytime you run into schmuck bait you know that things aren’t going to turn out well.

The truth is, for just about every stock Aesop warning about the perils of being overly nosy, you can find another one exalting it as a virtue. In fact, you could say that curiosity is a crapshoot.

But what is curiosity exactly? The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it as “desire to know,” and “interest leading to inquiry.” As you can imagine, there are situations where this could be good or bad. Thus, what a story says about curiosity often changes depending on its genre.

For example, in most horror stories, curiosity and nosiness are usually bad, leading the protagonists to go places where they shouldn’t and uncover things that should never have been uncovered. At the same time, a lack of curiosity can also be fatal … in fact, a lot of things can be fatal in a horror story.

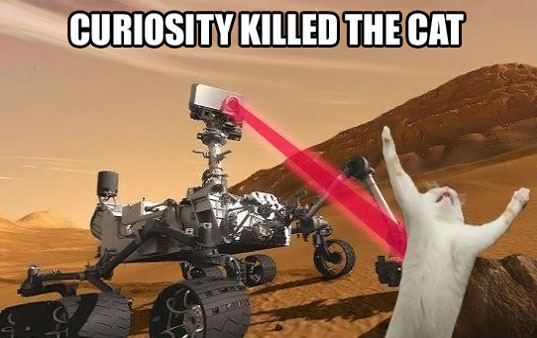

In mythology and folklore, curiosity is often even worse. From Pandora to Eve, Psyche to the proverbial cat, curiosity leads to Very Bad Things. Perhaps this is because these kinds of stories are mostly tales of warning, passed on from generation to generation as a way to preserve our collective knowledge about the dangers of the world, rather than inspire us to go out and face them.

(As a side note, there are a few exceptions in the realm of folklore. In the Bluebeard myth, curiosity killed off all of Bluebeard’s previous wives, but combined with cleverness, faith, and friendship, it saved the last one’s life.)

In fantasy, curiosity is often a mixed box bag. For example, take the hobbits: most of them are perfectly content to live out their lives in the shire, but the few who are inquisitive enough to venture outside end up saving the world in a way that the elves, dwarves, and humans never could. At the same time, it puts them through a great deal of pain, even after the world is saved–neither Bilbo nor Frodo are ever able to be content in the shire again.

Curiosity, in other words, is complicated. It’s not just a quirk or a character flaw–it’s an underlying quality of the hero’s journey. Without curiosity, either of the world around him or the internal struggles within, the hero would be content to live out an unremarkable life. Certainly he wouldn’t have the capacity for the cleverness, guile, wisdom, and sensitivity that he needs in order to descend into the darkest dungeon, face his own nadir, and return with the elixir of life. Curiosity may lead to sorrow, pain, or even death, but it also leads to adventure.

As a subgenre of fantasy, many of these issues carry over into the realm of science fiction. And yet, as a genre unto itself, science fiction has a distinctly positive view of curiosity compared to other genres. Science is nothing if not the primary process of human inquiry, where curiosity is not only a virtue but the virtue, one of the most important aspects of humanity. Consider these words from Adam Steltzner, one of the leading engineers of the NASA Mars Curiosity mission:

Likewise, curiosity is a staple of science fiction. In Star Trek, it’s the basis of the entire mission: “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no one has gone before.” In Doctor Who, it’s how the Doctor finds his companions. In Babylon 5, it’s Delenn’s curiosity about the humans that ultimately saves all the alien races. And in 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s the gift from the black monolith that helps monkeys to turn bones into space stations (well, not literally, but you get the idea).

Curiosity isn’t a central theme in most of my books, but it is a major part of Genesis Earth. If anything, that book is about the importance of balancing curiosity about our universe with curiosity about ourselves and what it means to be human. In Star Wanderers, Noemi’s curiosity is a huge part of her story, helping her to turn around a horrible (not to mention awkward) situation. In Desert Stars, curiosity is complicated; it leads Jalil far away from home and puts a schism between him and the girl who loves him, but it also leads him to discover the truth about who he is, giving him the strength to return.

In general, I suppose it all comes down not only to genre, but to the underlying worldview of the author of the story. Since I have a very positive and enthusiastic view of curiosity, it usually works out for the best in the stories that I write. Then again, perhaps that’s why I’m drawn to science fiction … how about you?