I recently read an amazing blog post by Shannon Hale titled “Why boys don’t read girls (sometimes).” In it, she makes a number of excellent points about how our society stigmatizes boys who read “girlie books,” and why that’s harmful.

I recently read an amazing blog post by Shannon Hale titled “Why boys don’t read girls (sometimes).” In it, she makes a number of excellent points about how our society stigmatizes boys who read “girlie books,” and why that’s harmful.

Perhaps the most moving part of the post was at the end, where she described an experience at one of her book signings where she saw a boy hanging back and asked him if he would like her to sign one of his books. The boy’s mother jumped in and said “yeah, Isaac, would you like her to put your name in a girl book?” The boy’s sisters all laughed at him, shaming him for reading anything that ran against their strictly defined gender roles.

In direct contrast to Shannon Hale, Dave Farland released a “daily kick” newsletter a couple of days ago where he advises writers to never let their characters cry. In it, he states:

Whatever problem [the character has]—whether terminal disease or sociopathic neighbor or anything else—the problem must be faced with courage. This means that your character can’t cry about it, no matter what the source of pain…Any time that a character breaks down, we as an audience may cast judgment upon that character.

Now, I have nothing but respect for Dave Farland. I’ve been following his “daily kick” emails for years, attended dozens of his convention panels, and even interviewed him once for an online magazine. He’s been a very influential writer to me personally, and his advice has had a huge impact on my writing.

But on this issue, I think he’s dead wrong.

Even if you don’t have any problem with the idea that men should never cry–a disturbing belief that harms men by forcing them to hide their true feelings, and harms women by teaching men that compassion and empathy are signs of weakness–even if you’re comfortable living in a culture that accepts this belief, there are still instances where having a man cry in your story can be both moving and poignant.

The best example of this that I can think of comes from David Gemmell’s The Jerusalem Man. No one–and I mean no one–writes manlier heroes than David Gemmell. And among his characters, Jon Shannow ranks as one of the manliest.

In The Jerusalem Man, Jon Shannow is a lone gunman roving the post-apocalyptic wastelands of Earth on a spiritual quest for the city of Jerusalem. Near the beginning of the book, he comes across a frontier woman under attack from bandits. He stops to defend her homestead, and she shows her gratitude by inviting him into her bed.

Jon Shannow is a middle aged man, but because of the post-apocalyptic setting, this is his first sexual experience, and it moves him to tears. For me, that was one of the most poignant moments of the book. It didn’t take away anything from his masculinity throughout the rest of the story–indeed, it added significantly to it when the woman got kidnapped and he determined to rescue her.

I’m sure there are other examples that you can think of. Certainly in real life, this notion that men should never show their feelings is both harmful and outdated. To say that in fiction, no characters should ever cry–female characters as well as male characters–that’s just so wrong it’s infuriating. If crying is so taboo that it’s even forbidden in the pages of a book, then something is wrong with the culture, not the story.

In 2008, I attended a fascinating panel at LTUE in which Tracy Hickman and a number of romance and fantasy writers discussed how to write romance in science fiction and fantasy. Tracy explained that in all the novels he writes with Margaret Weis, she does the fight scenes and he does the romantic ones.

He then went on to talk about how there’s a whole side of life that our culture has shut men off from–a feminine side which is present in all of us, men as well as women. The way he explained it, romance is not just the “kissy bits,” but a vital and enriching way to see the world–a paradigm that infuses everything with feeling and passion.

It makes me think of The Princess Bride, where even the action scenes with Inigo Montoya have a certain romantic flair to them. In the old days, the term “romance” described not only love stories, but action & adventure stories as well. In modern times, we seem to have forgotten all the old qualities like honor, love, sacrifice, loyalty, heroism, and compassion–even though they still make for the best stories.

It makes me think of The Princess Bride, where even the action scenes with Inigo Montoya have a certain romantic flair to them. In the old days, the term “romance” described not only love stories, but action & adventure stories as well. In modern times, we seem to have forgotten all the old qualities like honor, love, sacrifice, loyalty, heroism, and compassion–even though they still make for the best stories.

Of course, our characters need to have courage. But courage is not the absence of fear–it’s pressing on in spite of it. And crying is not always a sign of weakness–it can actually be a sign of great emotional strength. And if it’s true that the best literature helps us to see our world in a new light, giving us a greater understanding and appreciation for the human condition, how is it “courage” for anyone to hide their true feelings?

So do the characters in my stories cry? Hell, yeah! I don’t have them hide their feelings just because some readers might look askance. Some of them cry more than others, and many of them don’t hardly cry at all, but those who do cry do so because the story demands it.

Even though I write science fiction, I do my best to infuse my stories with romance–not just the “kissy bits,” but that depth of feeling and passion for life that made me fall in love with books and reading in the first place. Star Wanderers is a great example of that, and so is Desert Stars.

And yes, in case you’re wondering, I’ve read a lot of “girlie books.” They’re some of my all-time favorites.

I couldn’t agree with you more Joe. I also really respect Mr. Farland for his tutoring of Brandon Sanderson and many others, but I disagree 100%–in fact, the strength of my disagreement makes it tempting to not ever pick up a book of his (something I’ve been meaning to do for a while), as character growth and development is the single most important factor to me in a book. A book where certain forms of emotional expression are forbidden is terrible.

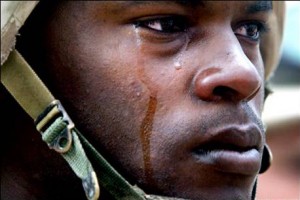

You said it really well here–and the picture of the crying soldier is icing on the cake. Nice work.

The argument I’ve always heard is, “If your character cries, the reader can’t. If your character laughs, the reader won’t.” I’m not sure that’s true….

This post may very well be my favorite.

Yes, absolutely, yes, we should see the entire spectrum of emotions. People laugh, rage, sputter, stand in awe, and yes, cry; to say that characters do not likewise is to admit that one does not even understand what it is to be human. /rant

Stephen, I wouldn’t shut myself off completely from Farland’s books. His first novel, On My Way To Paradise, is one of the best science fiction novels I have ever read. It would be a shame to miss stuff like that over a disagreement like this one.

Laura, I hadn’t heard that one. I suppose it’s true if you’re doing it wrong. It can be really hard to have your characters cry without seeming a little melodramatic, and I admit I’ve probably missed the mark a few times. But if I have to get it wrong, I’d rather err on the side of having them show real emotions.

And thanks, Benjamin! Glad you liked it. 🙂

If a character is so closed off from emotion he/she can’t/won’t cry then I’m probably not going to be able to relate to them. I want to read about real characters. And I think your so right saying that true courage is being afraid and knowing it but going ahead anyway to meet that fear. I’m currently reading a book written by a man in which the mc cries his eyes out and it made me care about him more, not less.

I’m with you on this 100% – there are always going to be people who disagree and different genre have different “rules.” But I don’t want my male characters to be wooden. They may have their ‘game face’ on at different times – but they should always be human enough to feel.

I think I have just as many reviews from men as from women – and I write Romantic Suspense. No one has complained about the scenes where my Male Leads break down. I’m sure someone might, eventually. but that isn’t going to change the way I write.

And my female characters also cry – in empathy, in loneliness, in anger, from frustration. Just like real people.

Even if you assume that readers won’t cry or laugh if your character does, sometimes that’s what’s needed for the story to work. Sometimes you want the reader “to cast judgement on the character”.

In other words, you don’t always want your reader to empathize with the MC. Sometimes, you just want the reader to sympathize with them. Or you want the reader to feel something completely different from the narrator.

For example, in one of my stories, the MC goes from freaking out to accepting a situation—and that scene has been described as “so funny but so sad” by readers, since the scene shows just how messed up that character is.

I’ve had characters have full-out mental breakdowns. Some get depressed, frustrated, etc.—male, female, I don’t care. If it fits the character and situation, it happens. And rather than complaining, readers have complimented me on my characters.

Empathy and sympathy are tools both.