A couple months ago, I was listening to one of my personal recordings of Brandon Sanderson’s English 318 lectures from last year’s class. The topic was writing characters.

A couple months ago, I was listening to one of my personal recordings of Brandon Sanderson’s English 318 lectures from last year’s class. The topic was writing characters.

Brandon outlined several techniques for making characters sympathetic. He also outlined how to round them out: give them flaws and handicaps, as well as little quirks to make them unique and memorable.

However, I couldn’t help thinking that something was missing in his formulation.

Before I continue, let me say that I’m not disparaging or criticizing Brandon Sanderson’s abilities to write compelling, well-rounded characters. As his novel Mistborn shows, writing characters is one of his strengths.

At the same time, I feel that the “checklist” approach to writing characters can be dangerously counter-productive. Too often, characters in sub-par novels feel like a patchwork of characteristics and personality traits, not like actual, real people.

When I asked Brandon about this, he said that his techniques should be seen as tools, not as fundamentals. He then went on to say that the most important thing to keep in mind is the character’s motivations–why they want what they want. Beyond that, you just have to tweak the character until they fit into their role.

After thinking about it for some time, I came to the conclusion that the best way to write characters is to keep two essential rules in mind:

Rule #1: Every character is the hero of their own story.

Rule #2: Every story is composed of three parts: beginning, middle, and end.

The first rule is straightforward: every character sees their life as a story in which they are the main character. This is because all of us, as human beings, view our own lives in this way. We may look at other people and consider them nothing but extras in the story of our life, but they certainly do not think of themselves in this way.

To apply this rule, however, we need to understand what it exactly means to be the hero of one’s own story. We can only understand this when we realize that a story is composed of three basic parts: beginning, middle, and end (or, as we see ourselves: past, present, and future).

Every hero has an origin and a destiny. Without these, they don’t have a story; they don’t have a beginning and they can’t have a meaningful end. This is why the hero cycle begins with the miraculous birth and ends with ascension and apotheosis.

Writers should keep this in mind as they sketch their characters. If you don’t know where your character came from–who their parents are, where they grew up, what were their major formative experiences, etc–your characters are going to fall flat because they’re just extras in someone else’s story; they have no story of their own.

Likewise, your characters need to have a destiny. If you’re a discovery writer (like me), this might be harder because you don’t know, from the outset, where everyone’s going to end up. Keep in mind, though, that rule #1 applies to the story the characters tell themselves just as much as the story you’re telling the reader.

Each character’s individual story is like a thread, which the writer weaves together with other threads to form a beautiful tapestry. That tapestry is the novel; without the individual characters’ stories, the work would feel week, shallow–threadbare.

Of course, it’s not always possible (or a good idea) to reveal everything about every character. It’s also not always possible to outline every character in great depth–not without catching “worldbuilder’s disease.” Instead, the rules of worldbuilding should apply–only use 10% of your worldbuilding in the actual story, no info dumps, etc.

I don’t think that’s a comprehensive theory of character just yet, but I think it’s a step closer to one. If you have any ideas or suggestions of your own, please do share.

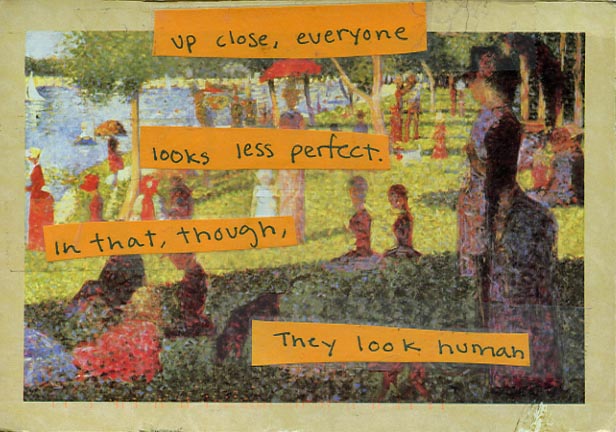

Image courtesy Postsecret

Agree with both your suggestions. I’ll also add that the best stories have their important characters change/grow in some way over the course of the novel.

The reader will probably hope for the protagonist to become a better person in some way, unless it’s a tragedy I suppose.

I personally get to know my characters a lot better while writing the novel, so that becomes something important to deal with during revision.