For the next few Trope Tuesday posts, I’m going to pick apart one of my favorite story patterns, the monomyth or “hero’s journey.” Other tropes come and go, but the hero’s journey is truly timeless. If you can get it to work for you, it can do wonders for your ability to understand and tell stories.

For the next few Trope Tuesday posts, I’m going to pick apart one of my favorite story patterns, the monomyth or “hero’s journey.” Other tropes come and go, but the hero’s journey is truly timeless. If you can get it to work for you, it can do wonders for your ability to understand and tell stories.

In many ways, this is the trope to end all tropes. it is the source of almost all the major story archetypes, and can be found in the myths and folklore of almost every human culture–hence the term “monomyth.” It was first formulated by Joseph Campbell, who outlined it in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. He summarized it like this:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

Campbell was an academic who studied mythology and folklore, and his book, though insightful, is pretty friggin dense (not to mention scientifically obsolete–he references a lot of Freud’s theories that have largely been discredited). Later, writers like Chris Vogler, Phil Cousineau, and David Adams Leeming analyzed and simplified the monomyth for popular audiences.

Enough background–what is it? Basically, it’s a story pattern that resonates powerfully with readers across all genres. In its simplest formulation, it follows three steps:

- Departure: The Hero leaves the familiar world.

- Initiation: The Hero learns to navigate the unfamiliar world.

- Return: The Hero masters the unfamiliar world and returns to the familiar.

Campbell himself identified 17 stages, some of which are interchangeable:

- Call to Adventure: The Hero learns that he must leave the familiar world.

- Refusal of the Call: The Hero balks, for any number of reasons.

- Supernatural Aid: The Hero receives something to help him on his quest.

- Crossing the Threshold: The Hero ventures into the world of adventure.

- Belly of the Whale: The Hero passes the point of no return.

- The Road of Trials: The Hero’s resolve is tested, and he begins to grow.

- The Meeting with the Goddess: The Hero experiences the power of love.

- Woman as Temptress: The Hero faces and overcomes temptation.

- Atonement with the Father: The Hero passes the final test.

- Apotheosis: The Hero dies and is reborn.

- The Ultimate Boon: The Hero receives a gift to take home.

- Refusal of the Return: The Hero doesn’t want the adventure to end.

- The Magic Flight: The Hero uses his newly mastered skills to escape.

- Rescue from Without: The Hero is saved by his newfound friends.

- The Crossing of the Return Threshold: The Hero leaves his new world.

- Master of Two Worlds: The Hero reconciles the old ways with the new.

- Freedom to Live: The Hero uses what he has learned to live the rest of his life.

Do any of those sound familiar? Yeah, I thought so. It might be hard to think of a story that fits all 17 points at once, but it’s not uncommon to find one that hits seven or eight (or possibly more).

A simpler formulation by Leeming goes like this:

- Miraculous conception and birth

- Initiation of the hero-child

- Withdrawal from family or community for meditation and preparation

- Trial and Quest

- Death

- Descent into the underworld

- Resurrection and rebirth

- Ascension, apotheosis, and atonement

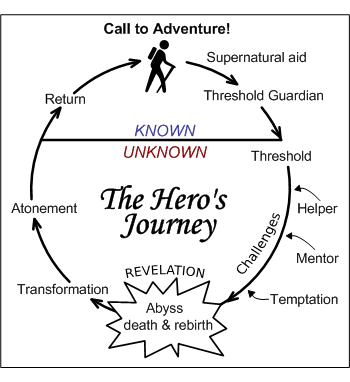

My personal favorite, though, is Vogler’s:

So how useful is this trope really? Well, consider this: Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game was the first novel to win both the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award in the same year…and it hits up all eight points listed above. The following year, Card published Speaker for the Dead, which also hit all eight points, and also won both the Hugo and the Nebula award.

The thing that made Star Wars more than just another campy sci-fi b-movie with (let’s face it) terrible acting and hokey dialogue is the fact that George Lucas drew so heavily from Joseph Campbell and the hero’s journey. Think about it: Luke Skywalker passes through almost every one of the 17 points, right up to the awesome throne room finale at the end.

Of course, it’s possible to go too far. Lucas also tried to use the hero’s journey in the prequel trilogies, and failed miserably. Why? Many reasons, but mostly because he used it as a rigid checklist rather than a dynamic set of flexible guidelines. The hero doesn’t have to have a literal miraculous conception; he just needs to be chosen in some way. The goddess doesn’t have to be literal, and neither does the father–those stages can be represented quite loosely, or merged with others.

In my own writing, I’ve found that the best way to use the hero’s journey is to use it to understand what I’ve already written, and to trust my subconscious to fill in the next step. In every book I read, or every movie I watch, I constantly pick it apart, looking for each of the steps. This trains me to recognize the hero’s journey in my own work without having to break out the hammer or force things too much.

So how do you use the hero’s journey in your own work? Do you find yourself hitting up all the points subconsciously, or do you use some other method? Or do you hate the hero’s journey and try to avoid it altogether? If you do hate it, I hope that my next few Trope Tuesday posts will help you to change your mind.

8 comments